Few places in the world have a relationship with literature as intimate and enduring as Iraq. The written word has long been a cornerstone of its cultural identity—a force that has survived empires, wars, and occupations. But in an era where truth itself is under siege, where journalism is suffocated by state and corporate interests, this literary legacy is more than just heritage, it is resistance. The same forces that tried to silence Al-Mutanabbi Street with bombs in 2007 are mirrored today in the global assault on storytelling. Nowhere is this more evident than in the headlines that contort reality as the siege on Palestine persists, even through Ramadan. The distortion of truth is an act of violence against history, a war against collective memory.

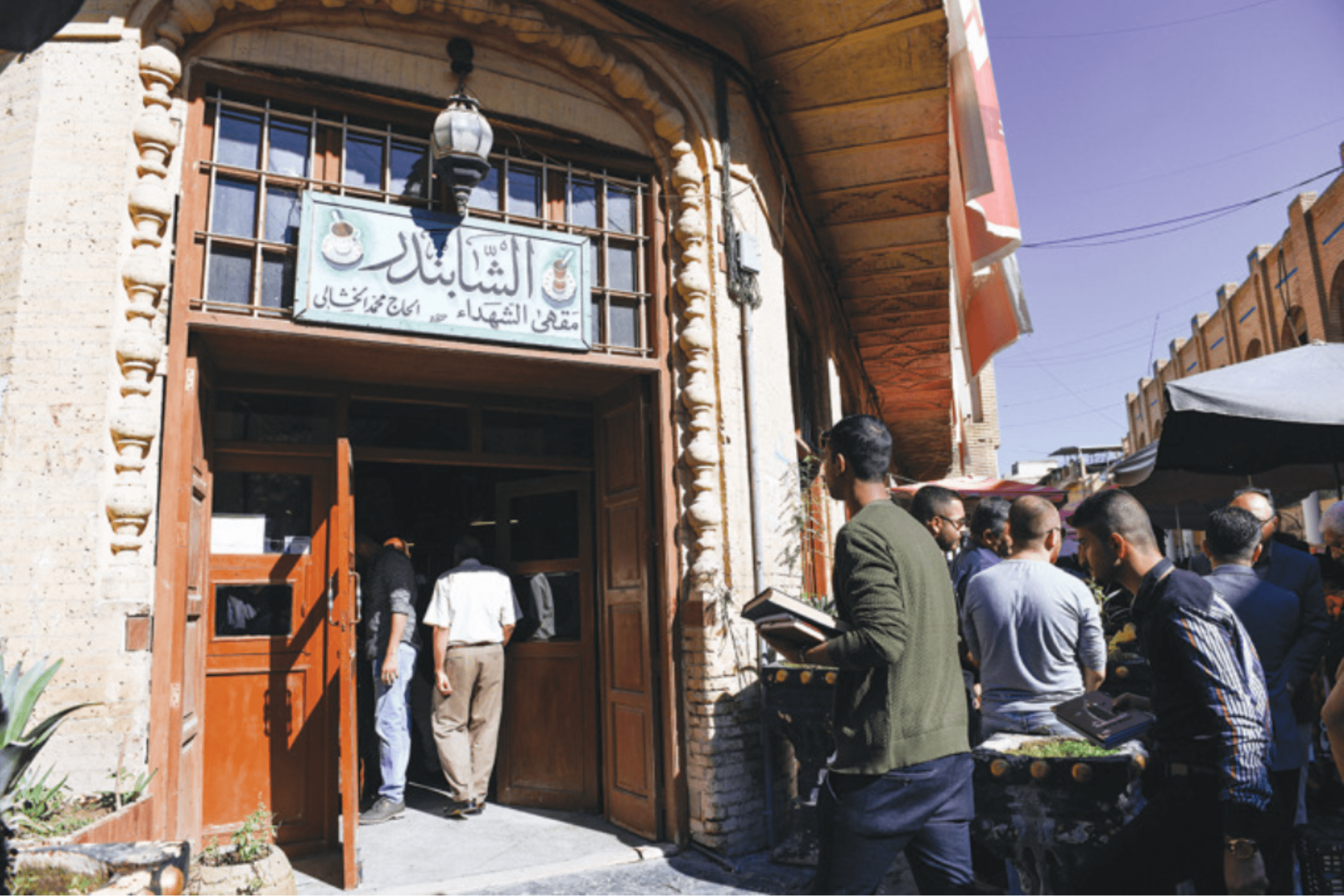

That being said, nowhere is more deserving of embodying this defiant literary spirit than Al-Mutanabbi Street, Baghdad’s historic book market and the beating heart of Iraq’s intellectual life. It is here, at its very end, that one of the city’s most beloved institutions has stood for over a century—Al-Shabandar Café. A sanctuary for poets, philosophers, and revolutionaries alike, its walls have borne witness to decades of conversation, ideation, and resilience.

On Saturday, 5th January 2025, Baghdad lost one of its great custodians of memory. Hajji Mohammed Al-Khashali, the owner of Al-Shabandar Café, passed away at the age of 93. His name was synonymous with the café itself, a man who spent decades preserving its spirit even after unimaginable loss. His passing marks the end of an era, but his legacy, much like Al-Mutanabbi Street, will endure.

Last summer was the first time in my life that I was able to visit my mother’s home country. On my second morning in Iraq, I am taken to a place which physically honours the popular saying “Cairo writes, Beirut prints, and Baghdad reads”. Al Mutanabbi Street is a historic locus of ancient literature in the old quarter of Baghdad. Booksellers have been setting up stalls and selling all types of literature along these lanes for decades. Named after Abu Al-Tayyib Al-Mutanabbi, a 10th-century poet whose famous words on war, love, and courage rippled through society, the street today is busier than ever and a tourist favourite.

So, on that morning, a cultural sphere nurtured by lifetimes of Middle Eastern intelligentsia is now before me, and I stop at every chance to explore. On Al-Mutanabbi Street I am offered pomegranate juice and books, and prayer beads for free.

A short walk from the street is the even more famous Shabandar coffee house. Over a century old, the walls of Shabandar bear witness to decades of conversation and theorising. For years, this large café, and its walls which are lined entirely with portraits of famous politicians, philosophers, and teachers from across time, has hosted Iraq’s intellectual community. Writers and poets of all faiths recited their work here, and respect for differing beliefs was a major principle inside Al-Shabandar. Once the tea is served, there is no conflict between your God and mine and this solution. This is now a safe space where the ritual phenomena of oneness emerge. I don’t drink until you do, but you’ll always wait for me.

To sit and have chai in Al-Shabandar is to slot yourself into a page of history. The faces that decorate the walls reflect the diversity of those who have gathered here over time, shaping our understanding of philosophy, medicine, astronomy, politics and movement. I stare into the eyes of each portrait, thinking of the ideas and philosophies behind them. In this moment, I realise I am the inheritor of a legacy so expansive that it would be an affront to my ancestors to assume I don’t belong where they once stood. We diaspora are often contemplative of our ability to claim and indulge in our home cultures. But here I realised that no matter how migration has shaped your story, as a child of Iraq, if you make it to Shabandar, you belong in Shabandar.

Back in 2007, amidst sectarian conflict, a car bomb exploded in Al-Mutanabbi Street, claiming 30 lives and injuring over 100 people. It destroyed Shabandar. Hajj Mohamed Al-Khalili, the 90-year-old owner, lost four sons and a grandchild in the explosion. The intellectual community was silenced, the Iraqi love of thought and knowledge was threatened, and Al-Mutanabbi Street was abandoned as though the books themselves were immobilised with grief. The reverberations of this attack were felt around the world, as it spoke volumes on censorship. The attack devastated Baghdad and the world.

My elder cousin, Seif, who I met for the first time in my life that morning, shows me a photo of his brother as we chat over dried lime tea, ‘chai noomi basra’. His brother lost his legs in the attack. He was sitting in the same seat, drinking the same tea as we were when it happened. I stare in silence. He showed me photos of his brother with his wife and child in Finland, confidently standing with his prosthetic leg. Everyone in the picture looks so incredibly happy, and I take his phone in my hands, staring hard at the picture. Hardships do not deter the Iraqi people.

Despite his unshakeable grief upon losing his four sons and a grandchild, Al-Khalili was determined to rebuild Shabandar. His pain is palpable, it is in his every word, but it seemed Al-Khalili alchemised his grief into the redevelopment of the coffee house, because on the morning I am there, the soundscape is woven with clinking of glasses and rapid Iraqi chatter, echoing stronger than ever before. Now, of course, Al Khalili’s four sons are amongst the faces that guard the walls as we carry on the conversations we inherited from them.

In the short film Forgive but Never Forget directed by Hiwa Osman and Amal Al-Jubouri, Hajji Mohammed Al-Khashali sits before the camera, his words slow, deliberate, as if speaking them out loud might reopen the wound. He recounts the moment the bomb tore through Al-Mutanabbi Street, ripping apart not only his café but the lives of those who had made it their second home.

“Eighteen of the street’s regulars,” he says, pausing as if seeing their faces before him, “booksellers, vendors, shopkeepers… we could not find any trace of their remains.” He closes his eyes for a moment. “The stories of devastation make the heart bleed.”

He remembers crawling out from beneath the rubble, choking on dust and debris, and calling his sons’ names. “Mohamed… Kadhem… Bilal… Ghanem….” He repeats them, one after the other, as though even now, they might still answer.

The street he had known his entire life was unrecognisable, with blood pooled between shredded pages. The missing were impossible to piece together; bodies had been scattered, disfigured beyond recognition. “The next day, we returned to search for them,” he recalls. “The good people of Baghdad brought their pickups to help.” It became clear what happened to Mohamed, Kadhem, Bilal, Ghanem and Ghanem’s young son, who died in his arms.

The silence between Al-Khashali’s words stretches long, each pause a moment of mourning in itself. He does not weep, but his voice carries a sorrow deeper than tears.

“Their mother… may Allah have mercy on her soul.” She did not survive them for long. She spent her final days calling for them, seeing them in the shadows of their home, hallucinating their presence. “She would talk to them, tell them to come inside,” he says. “And then, she too was gone.”

The wives and children his sons left behind became his responsibility. He built them homes on land close to his own, keeping them close, ensuring they would never feel abandoned. He raised his grandchildren, watched over their education, did everything a father should, and proudly spoke of the success of his grandchildren as Pharmacists and students in Medical school. And then, with the same resilience that had always defined him, he rebuilt Al-Shabandar. “Some people helped me rebuild the coffee house again, and I placed myself in the hands of Allah.”

Learning of Hajji Mohammed Al-Khashali’s passing has altered my memory of meeting him. There are moments that feel unremarkable in real-time, only to inherit profound weight in retrospect. I didn’t know, when I first met him that morning in May 2023, that I was meeting the very soul of Al Shabandar Coffee House—the man who preserved its legacy through war, grief, and renewal.

Some people spend entire lifetimes trying to learn how to forgive, how to grow from the pain pitted deep in our stories, but Al-Khashali’s way of being was something we all ought to learn from. The documentary’s concluding words from him are, “Because I care for my country, which is bleeding, and because I am Muslim, if the killer of my sons was brought before me and swore to never kill again, and to defend Iraq with his life, then I will forgive him.”

Our exchange that morning was fleeting but vivid. I had been admiring an old vinyl player in the corner of the café, taking photographs of it. He turned to my cousin and quipped, “Does she know it costs 100,000 dinars to take a photo?” I caught his smile and replied, “That’s a shame because I only have 90,000 on me.” He laughed, “Habibti,” and gestured for us to enjoy our seats.

Now I know that when I return to Baghdad, inshallah this October, I will walk into Al Shabandar knowing he will not be there to greet me—or any of the tea drinkers who pass through its doors. But his presence, like the spirits of those who came before him, will linger. His sons watch over the café from their frames on the wall. Soon, he will join them—the fifth portrait in the row, framed eternally, the guardian of a place that, epitomic of the Iraqi spirit, perseveres.

(Words by Yasmin Alrabiei)